DISEQUILIBRIUMS. The Individuals. Chapter 7

CHAPTER 7

Thursday 15 December 2016

Time: 11:00

Going into a museum is normally really boring, especially if you don’t have a clear mission. It was my dad who made my brother, sister, and me look for something more in such places. Not that we had not travelled a lot in our lives. In the past two years during the summer holidays, we had been to England, France and Italy in the same summer, at my dad’s insistence. The truth was that it wasn’t so dictatorial of him, because when he first brought it up, we all thought it was a very good idea. Three different countries in the same summer, great! That was my initial thought when he said it.

The five of us had always made decisions on where to go together on holiday, until this last summer. One day in May, we would agree on a time when each member in the family could propose where to go and what to do. I had always thought that my parents were a little strange. When I asked my friends who else did this, I realised that they were unique. In none of my friends’ families did they do something similar. I liked the idea because each of us could make a suggestion and we all ended up laughing. It was very good, especially because I realised in later years that they did it so that we would learn geography. We had to give a presentation to the others using maps showing where we wanted to go. Initially, in earlier years, we used an atlas, but later on we had to design the holiday in front of a computer screen, using the internet to look at, move and enlarge maps as much as we wanted.

So, two years ago, when he suggested it, his proposal was successful and we had a very good time. The strange thing was that, the following year, he suggested the same thing. However, this time, he proposed that we visited the three cities where we had spent the most time the previous year: London, Paris and Bergamo. He put it to us in such a way that night, that my brother, sister, my mother and I all looked at one other in surprise. We weren’t able to come up with another suggestion.

So we returned and had a great time once more.

However, there was something that was different from before. I remembered that in the second year, my dad disappeared for a whole day in each of the three cities and he never told us what he had done on his free Father’s Day, as he called it to justify it. My mother didn’t seem to mind because it was clear that she knew what he was doing. They really got on very well, although they were very different people. One was like the mountain and the other like the valley. But that was the most special thing about them because they always came to an agreement.

The problem is that the summer last year was the last time we would have a holiday together.

What I remember most of the visits to those three cities were the museums he took us to. We went to the most important ones and in each he invented a kind of treasure hunt. I will never forget when, in the middle of the National Art Gallery in London, as she entered the room, my middle sister shouted out, “a Van Gogh!” Everyone in the room turned around to look at her. We felt embarrassed, but our parents were full of pride.

They made everything seem special. When we visited Paris, we had to draw the facade of the Notre-Dame Cathedral and count how many statues and geometrical shapes there were. And we did it, although I have to admit that it was a condition they gave us for going to Disneyland the following day. We of course completed the task without complaining.

But I never got to go with him to the Zaragoza Municipal Museum, (also called the Provincial Museum). The most important and the oldest one in the city we had never visited it together. I wondered what kind treasure hunt he would have organised for us there. I would never know.

At least, he taught us to enjoy looking for things which others might overlook. A typical question we would hear him say when we visited a museum was: “How many people do you think would have noticed that?” So, today, I pause for a long time to look at a large stone in the museum.

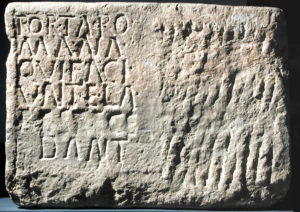

“Piece of Roman ashlar”, is preserved in Museum of Zaragoza

Name of the photographer: José Garrido Lapeña

As the sign said, it was a piece of an ashlar from the East Gate of the Roman city, which they later called the Valencia Gate. The explanation is on a small white card next to the stone. It’s a quadrangular piece of masonry, worked in grey limestone, 80 cm wide by 57 cm tall and 91 cm thick. On the left side of the face there are some inscriptions in six lines of Roman lettering. I try to read them, but not all the lines are complete. On the right side, there is no inscription. Yet it’s obvious that something used to be there because the face is worn away as if by some kind of tool which had erased what there was, making it illegible.

Suddenly, all that slips from my mind when the guide comes up and speaks to me. I don’t know what surprises me more, her words or when I shake her hand, I notice a crumpled paper left in my palm after we release our hands as she says goodbye with a conspiratorial smile.

For a moment, I remain frozen, incapable of moving. Then, I turn around. I remain standing alone next to the stone that I was studying. The guide has disappeared and my friends are looking at me some metres away. For a moment, I think that she is probably mad. On the other hand, the way she looked at me and spoken to me was that of someone who was totally sane, but she had a certain air of mystery about her.

Looking at the people around me at the time, I see that the museum guard has noticed what happened. I don’t think he’s seen the paper, but he’s calling someone on his mobile. He’s looking at the guide. Our eyes met and, without taking his eyes off me, he speaks very briefly on the phone. Whatever was said to him must have made him uneasy because he quickly looks away and disappears once more through the black curtains to the room with the mural of the city. I continue standing in the patio next to the monolith. My friends have not budged from where they are standing and are still looking at me.

I open the paper and read its contents. Below some text, there is a drawing of a circle and within it a rectangle in which there are lines linking two halves of a rectangle. A small figure formed by the two squares is located where the inner lines met. What strikes me most is that, compared to the sides of the paper and the text above it, the rectangle is tilted a little to the right.

I don’t know what to make of it. My friends keep looking on. Just then, there is a commotion as two groups of tourists come together, one finishing their guided tour and the other about to start. We find ourselves among a crowd of people and I’m totally amazed to see Elsa, with great skill and effort, make a perfect pathway between the two groups for us to leave the museum.

She’s incredible. The next time I find myself trapped in a crowd of people, I would want Elsa next to me.

“Thanks a lot,” I say, with a wink, when I catch up with her.

It probably helps that she’s so big and tall (in fact, she was as tall as Erik and was a key player in her basketball team), with her dark complexion contrasting greatly with that of the other people there. Moreover, she’s wearing a long black coat, a white woollen cap with a visor covering her hair. Having put up her collar, she has a certain air of importance. When she stretches her arms out between everyone for them to make way with a big smile on her face, everyone moves aside and regards her seriously. By the expression on their faces, they think that she’s part of the museum staff.

Suddenly, the guard, who was inside earlier, comes up from behind her, seizes her hand and whispers something in her ear. With a grimace of pain, Elsa pulls away hard from him to escape his grasp. She makes a gesture as if she doesn’t understand, which isn’t surprising, given all the hassle taking place. The man is now speaking louder, and so I go closer to hear him.

“Take your friend away from here immediately and take no notice of anything she tells you!”

Swinging her arms amid other people’s shouts and shoves, Elsa manages to free herself from the man. She looks at him, frowning with hostility as he slips away, disappearing from sight. She looks my way, wide-eyed, lowering her arms and allowing the crowd to carry her along towards the exit. We both shrug our shoulders.

The crowd drag us along until we find ourselves together at the entrance.

“What shit is this?” Elsa asks me, straining every muscle on her face. “Who’s that guy?”

“I have no idea,” I reply.

From her expression, I can see that she’s as confused as I am.

With everyone’s nervousness, what happened with the guide and afterwards the incident with the guard left me quite confused and so distracted that as I leave the museum I stumble over two well-dressed people who have collapsed in the street. I almost scream out of fear, but I manage to control myself. This is madness. What’s happening to this city? I turn to the guard at the door, pointing at the people on the ground. He merely shrugs his shoulders, shortly before raising his hand to his ear and closing his eyes as if something was suddenly irritating him. The moment quickly passes, although I can see a drop of blood trickling down from his left ear. He stops looking at me and, in the confusion, tries to help the two groups entering and leaving at the same time. Unable to do so, he finally sits down on the chair behind him.

If I am surprised, it’s nothing compared to Elsa and David. Erik is less expressive, but I think that, deep down, he’s as disconcerted as we are. We look all around us. On every corner of the plaza, there’s someone on the ground.

“What’s happening here? Everyone’s collapsing in the street,” David remarks.

“What shocks me more,” Elsa responds, “is that the passers-by don’t seem at all surprised by all the people who have collapsed.”

“No adult seems bothered. We shouldn’t let it bother us either,” I say as we left the museum. “Let’s finish the work we have to present before Christmas.”

At that moment, everyone turns towards me and stares at me without a word. I take out the paper that the guide at the museum gave me. They look at the crumpled paper on which, as I smooth it out, they can see what’s printed on it: Calle Mayor 1, 8th Floor, and the symbol.

They all look at me and David asks:

“Apart from giving you the note, did she say anything?”

I remain pensive for a moment, and after a moment’s silence, I repeat the precise words the guide said to me: “Visit him. He will give you the answer,” I quote word for word.

Writer: Glen Lapson © 2016

English translator: Rose Cartledge

Publisher: Fundacion ECUUP

Project: Disequilibriums

Register on the website www.disequilibriums.com/en/registred and you will receive a notification to allow you to read the chapters as they are published and updates of the project.

No Comments